By 2025, IP traffic volumes will triple, but revenues will be fairly flat3 due in part to falling Mbps prices.

Access to internet content and applications by internet users mobilizes many wholesale players who constitute the internet connectivity ecosystem. These players provide and use IP transit and content delivery solutions. However, the market is poorly regulated: the balance between various players is essentially based on the negotiating power of each and on technical and economic arbitration between the relative cost of the various options and the quality of service. What levers do these players use to serve their interests?

Internet connectivity is a very hierarchical market

The foundation of the internet is the interconnection between several types of players

The main players in the IP connectivity value chain are:

- Internet service providers (ISPs) who deliver traffic to end users,

- Content and application providers (CAPs) who produce content and then distribute it through third parties,

- Forwarding agents, who route data and enable all players to access the entire internet,

- Content delivery networks (CDNs) that allow content to be distributed as close as possible to the endusers, notably through local caching solutions.

These networks are interconnected and crossed by bidirectional traffic flows, with each player deciding which network to send its traffic to, via a transit or peering agreement.

In a transit agreement, an operator-provider offers global connectivity to an operator-customer and routes all traffic to and from that customer.

In a – mostly informal – peering agreement, two "peer" players of comparable size exchange traffic to and from their respective customers. Peers are thus both customers and suppliers to one another, and generally do not charge each other because it is in their mutual interest. Peering is said to be private when the interconnection takes place on the premises of one of the peers, or public when the two players use internet exchange points (IXPs) located in the interconnection datacenters.

The evolution of usage has led to the dominance of certain players

Today, internet service providers, with their millions of internet users or "eyeballs1" rarely a match for the forwarding agent and content providers who address a much larger audience. Half of the international bandwidth is used by a few major content providers, notably the GAFAMs2. Some small players with little bargaining power have no choice but to pay one or more forwarding agent in order to connect their customers to the internet. All internet players are unofficially divided into several groups according to their interconnection relationships:

- Tier 1 networks are at the heart of the Internet. They are a circle of about 20 players who have established peering agreements with each other, giving access to all internet routes;

- Tier 2 networks have peering relationships with networks that are geographically close, and pay transit to Tier 1 networks to benefit from global connectivity;

- Tier 3 networks rely entirely on transit and have one or more providers.

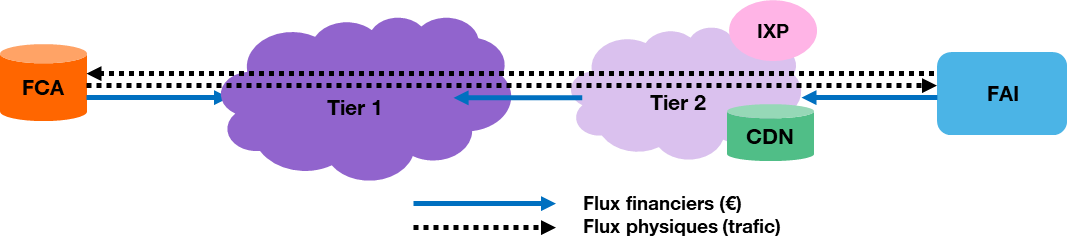

Scheme of the main players in the IP connectivity market and the flows exchanged

Thus, each player is obliged to evolve to remain competitive in this hierarchical ecosystem, where content providers have increasingly hegemonic positions.

Players implement their own strategies to optimize their P&L

The internet is still growing steadily. By 2025, IP traffic volumes will triple, but revenues will be fairly flat3 due in part to falling Mbps prices. Markets remain highly dependent on transit, especially emerging markets. In this context, how can we grow transit revenues while limiting associated expenses?

A peering agreement is a preferred solution for many players

Peering allows traffic to be exchanged without having to go through transit providers, and thus move up the ladder in the Tiers pyramid.

Peering policies displayed by the various players reflect their willingness to win, or not, peers: while new entrants tend to display an open policy, others are often more restrictive and set certain criteria for establishing a relationship (e.g., minimum threshold of traffic to be exchanged, minimum number of points of presence around the world, etc.)

The strategies for gaining peers are numerous. For example, a player that buys several products from a provider (IP transit, fiber access, etc.) can negotiate a free peering agreement as part of an overall commercial agreement. Other players will get closer to the larger ones by establishing paid peering agreements: in this way, the small player will be seen as an equal and will strengthen its bargaining power. Some Tier 2 networks aim to establish peering at all costs with all Tier 1 players to try to enter this very closed circle, even if all agreements would have to be free to truly be part of it. Other Tier 2 networks will develop a logic of bypassing Tier 1 in order to retain control of their routes and traffic.

Nevertheless, peering creates a potentially unstable situation between the two partners, on the one hand because of traffic imbalances that may arise, and on the other because of the potential competition between the two partners with their respective transit customers. Before establishing a peering agreement, the player must take these elements into account and not underestimate all the associated costs: infrastructure costs, recruitment of network engineers to manage these interconnections and ensure quality of service, IXP membership costs, etc.

In the end, the very low cost of IP transit in some regions such as Europe or North America makes it not necessarily profitable for a player to switch its traffic to peering interconnections.

The current trend in the IP connectivity market is towards convergence

ISPs want to facilitate content access for their internet users. To achieve this, some ISPs are following a diversification logic by developing their own content platforms and their own broadcast platforms. Others are establishing partnerships with CAPs (e.g., zero-rating4 which consists of offering internet users free access to certain contents, not deducted from data packages), or even succeeding in monetizing access to their internet users (e.g., by setting up a data termination paid by the CAP or the forwarding agent in order to route the traffic more easily).

To bring content closer to users, CDN solutions are booming: IDC estimates that CDN revenues will double in 5 years to reach 16 billion euros in 2025, while over the same period, the IP transit market will only grow by 26% to reach 4.6 billion euros according to Telegeography. CDNs will carry 72% of total internet traffic by 2022. CDNs represent a generally beneficial solution for all players in the IP chain, from traffic enhancement to bandwidth savings. Thus, some CAPs, forwarding agents, or ISPs are developing their own CDN solutions. Caches can be directly installed with ISPs to be closer to internet users, allowing negotiations to know if one of the two parties will pay for the hosting of the infrastructure.

Thus, the prospects of the IP transit and CDN markets are forcing players to adopt a convergence logic to respond to the evolution of usage. The context is ultra-competitive, so partners are also competitors, which weakens relationships and forces them to constantly innovate to balance their P&L.

1 "Eyeballs” are Internet users who primarily browse content

2 In France, 40% of ISP traffic will come from Netflix, Google and Facebook in 2020 (Arcep)

3 Telegeography estimates that IP transit market volumes will grow from 650 Tbps (2021) to 1650 Tbps (2025), but that IP transit revenues will be tempered by a significant drop in prices and will grow from EUR 3.8 million (2021) to EUR 4.6 million (2025).

4 Zero-rating is forbidden in some countries, as this practice goes against net neutrality, which provides for an undifferentiated treatment of all content, regardless of its nature